Rifling Impressions

A

bullet is slightly larger in diameter than the bore diameter

of the barrel in which it is designed to be fired. The bore

diameter is the distance from one land to the opposite land in a

barrel. As a result, a rifled barrel will

impress a negative impression of itself on the sides of the bullet

like those seen below.

The rifling

pattern in the barrel that fired a particular bullet can be determined

by counting the number of groove

or land impressions around the circumference of the bullet. Then, by holding the

nose of the bullet pointing away from you, the direction the

impressions run away from you (either to your left or right)

determines the direction of twist. If the rifling

impression pattern on the bullet matches the rifling pattern in the

barrel of the questioned firearm, the next step is to measure the

rifling impressions on the bullet.

The lands and grooves

on a bullet are measured in thousandths of an inch or in

millimeters. One

way to measure individual rifling impressions is to use a micrometer

like the one below. The right image below shows the micrometer

positioned next to a land impression on a bullet.

This is

important because even though the rifling pattern may match between

the bullet and questioned barrel one 6/right rifled barrel can have lands and grooves

of a differing width than another. The

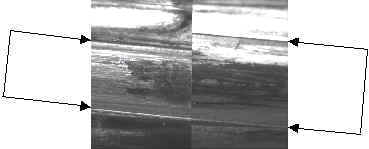

image below shows the land impressions on two bullets. Both were

fired from 6/right rifled barrels. The land impressions are

lined up at the bottom edge but as you can see, the upper edges do not

line up because the land impression on the right bullet is wider.

The widths of the lands

and grooves on a bullet provide a further class characteristic that can

be used as a preliminary means to determine if the submitted bullet

could have been fired from the submitted firearm.

Another

class characteristic of rifling that is seldom comes into play is the rate

of twist or pitch of the rifling in the barrel. The

rate of twist is the distance the rifling needs to spiral down the

barrel for it to complete a single revolution. An example would

1 turn in 12 inches. The term pitch refers to the angle at which

the rifling is cut in the barrel. The two images below show the

rifling in a 5 inch barrel on the left opposed to a 1 3/4 inch barrel

on the right. Note the difference in pitch of the rifling.

The barrel on the right actually has very little pitch to the

rifling. Depending on which way you look at it the direction of

twist could be to the right or left. It is a 10/right rifled

barrel.

When

bullets are compared to standards from a given barrel the pitch to the

rifling impressions can be a means to eliminate the bullet as having

been fired from the firearm. If the angle disagrees with the angle

found on standards then the comparison will be a negative one based on

those class characteristics. The problem with this is that it is

hard to accurately measure the pitch. Unless there is a noticeable

difference in the pitch, it can be hard to use this class characteristic

as a means of elimination. As a result, firearm examiners rarely

measure the rifling impression pitch. The two bullets below were

fired from different 6/right rifled barrels but the pitch is

different. Not by much though and any damage to a bullet like this

could make the difference difficult if not impossible to see.

Firearm examiners can run into problems determining any of the previously

described class rifling

characteristics on the bullet if the bullet is damaged like the one seen

below.

You may get a bullet fragment that

only has one or two land and groove impressions and the

direction of twist may not be obvious.

Therefore, here is where a little math comes in. Let us say you have a fragment with only

one land and one groove impression visible (the minimum number for

this to work). You measure the land

impression width to be .055 inches and the groove impression width to

be .130 inches. Divide the diameter of the bullets suspected or

measured caliber, in this case .357, by the sum of the width of the

one land and groove impression (.185), and then multiply that number

by pi (3.14).

.357 / .185 * 3.14 = 6.05

This

will give you the approximate number of lands or grooves that would have

been in the barrel that fired the bullet. In this example, the

approximate number of lands and grooves would be six.

If a

bullet is badly damaged and exhibits poor class characteristics not all is

lost. There is still a possibility that some unique

microscopic marks from the barrel still exist on

the surface of the bullet.

Click

the Next button below to continue.

|